When acquiring an image, precise control over the duration of the exposure is critical. While camera settings allow us to define an exposure time, the underlying photoelectric effect itself is not something we can directly switch on or off. Photons striking a sensor pixel will generate photoelectrons continuously, and those charges will accumulate in the pixel well unless a mechanism exists to define when integration starts and ends.

Shuttering is the mechanism that performs this control. In scientific cameras, shuttering is not simply about blocking light—it defines the effective time window during which photoelectrons are allowed to contribute to the measured signal. How this window is implemented, whether mechanically or electronically, and whether it is applied uniformly across the sensor or sequentially in time, has direct consequences for image distortion, synchronization, and quantitative accuracy.

This article examines how shuttering is implemented in scientific imaging cameras, the practical differences between rolling and global shuttering, and how these choices affect real-world imaging applications.

What Is Shuttering in Scientific Cameras?

In scientific imaging, shuttering defines the time interval during which photoelectrons generated in the sensor are allowed to contribute to the measured image signal. Because photon arrival and photoelectron generation occur continuously, shuttering does not control when light reaches the sensor—it controls when accumulated charge is considered valid data.

At the pixel level, photoelectrons will continue to accumulate in the pixel well unless an active mechanism establishes a clear start and end to integration. Shuttering provides this temporal gate, defining the effective exposure window for each image frame.

Importantly, shuttering in scientific cameras is a system-level function rather than a simple exposure setting. It is determined by sensor architecture and readout timing, and it may be applied either uniformly across the sensor or sequentially in time. These differences affect temporal alignment within the image and can introduce distortion, synchronization challenges, or timing offsets that are critical in scientific and quantitative imaging applications.

How Shuttering Is Performed: Mechanical vs Electronic

Mechanical Shutters

Figure 1. Mechanical shutter

The mechanical shutter is used to physically block more light from reaching the sensor to end the frame's exposure, and allow the readout process to take place in darkness. Their movements often take place faster than the human eye can see.

Historically, unwanted light was blocked at the sensor using a mechanical shutter that physically covered the detector before and after an exposure. In such systems, the shutter opens at the start of the selected exposure time and closes again to end integration. This approach remains common in many consumer DSLR and mirrorless cameras.

In scientific imaging, however, mechanical shutters present fundamental limitations. The presence of moving parts introduces vibration, limits repetition rate, and imposes maintenance and lifetime constraints. More importantly, mechanical shutters are poorly suited to the short exposures, high frame rates, and precise timing control required in many scientific applications. As a result, they are rarely used as the primary exposure control mechanism in modern scientific cameras.

Electronic Shutters

Electronic shuttering addresses these limitations by controlling exposure at the pixel level using transistors integrated into the sensor architecture. Rather than physically blocking light, electronic shutters manage the flow of photoelectrons within each pixel.

By acting as electronically controlled switches, pixel transistors can direct collected charge to ground (resetting the pixel), to a storage or masked region (as in global shutter sensors), or into the readout circuitry for measurement. In this way, electronic shuttering shifts exposure control from a mechanical barrier to precise, high-speed timing control in the charge domain, enabling the exposure strategies required for modern scientific imaging.

Rolling vs Global Shuttering: Timing and Exposure Differences

Electronic shuttering defines how exposure is applied across a sensor in time. In scientific imaging cameras, the two dominant timing strategies are rolling shutter and global shutter, and the difference between them lies not in how long the exposure lasts, but when different pixels are exposed relative to one another.

Rolling Shutter

In a rolling shutter architecture, exposure is applied sequentially, typically on a row-by-row basis. Each row of pixels begins and ends its integration at a slightly different time, following a fixed temporal offset as the shutter “rolls” across the sensor. Although all rows may share the same nominal exposure duration, their integration windows are not temporally aligned across the sensor.

This sequential timing has several important consequences. Motion within the scene, or changes in illumination during readout, can lead to geometric distortions, skew, or banding artefacts. In static or slow-changing scenes, however, these effects may be negligible. Rolling shutter designs are also often favored for their simpler pixel structures, which can offer higher fill factor and sensitivity—advantages that are particularly relevant in low-light scientific applications.

Global Shutter

Global shuttering applies the exposure window to all pixels simultaneously. Every pixel begins integrating at the same moment and stops integrating at the same moment, ensuring temporal uniformity across the entire image. This approach preserves geometric integrity when imaging fast-moving objects or when precise timing alignment is required.

To achieve this, global shutter sensors typically incorporate additional in-pixel circuitry, such as charge storage nodes or masked regions, allowing collected photoelectrons to be temporarily held before readout. While this added complexity can reduce effective fill factor or sensitivity compared to rolling shutter designs, it provides deterministic timing that is essential for high-speed imaging, synchronized illumination, and multi-camera systems.

Both rolling and global shuttering represent different approaches to applying exposure timing across a sensor, each involving trade-offs in temporal alignment, sensitivity, and pixel complexity. In modern scientific cameras, these shuttering strategies are most commonly realized as CMOS Electronic Shutters, where the timing behavior is tightly coupled to pixel architecture and readout design.

Rolling Shutter Artefacts: When Do They Matter?

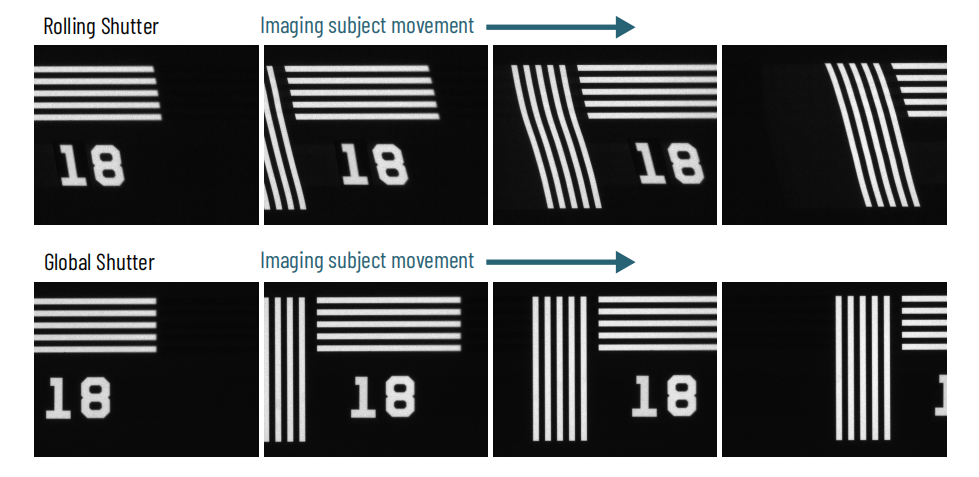

Figure 2. Rolling shutter artefacts due to moving imaging subject

This test slide is moving from left to right past the camera at a speed that is fast enough to cause rolling shutter artefacts: by the time the rolling shutter moves on to the next row of pixels, the contents of that row has moved a significant distance.

For many applications, the rolling shutter operates too fast to be perceptible or ever present an issue. In static scenes, or where motion and illumination changes occur slowly relative to the sensor timing, rolling shutter artefacts such as geometric skew, distortion, or banding may never become an issue. For others, however, global shutter behavior is essential.

An idea of whether or not a rolling shutter would interfere with your imaging application can be gained through the calculation of the sensor timing. Most sCMOS sensors have a line time between around 5 and 20 μs, depending upon camera speed. The delay between any two rows is given by the number of rows between them x the line time. The maximum delay, between the top and bottom of the sensor, is simply given by the inverse of the frame rate – e.g.10ms for a 100fps sensor.

Rolling shutter artefacts become relevant when scene motion or illumination changes occur on timescales comparable to these row-level or frame-level delays. If this level of delay, either on the singlerow lengthscale or whole-sensor lengthscale, might interfere with your imaging, it is worth calculating the exact values of delay for your sensor in the mode you would intend to use.

Minimum Exposure Time Limits in Rolling Shutter Sensors

Rolling shutter sensors do not prevent short exposure times at the individual row level. For applications that require a short exposure time, rolling shutter cameras can introduce issues, unless the use of a pseudoglobal exposure is possible. While the minimum time that each line exposes is the line time, these exposures start sequentially for each line.

The actual time that the camera is exposing is given by the exposure time plus the time taken to roll down the sensor. Rolling shutter cameras therefore have an ‘effective’ minimum exposure time equal to the frame time.

This distinction is particularly important for applications involving pulsed illumination, fast transient events, or tight synchronization requirements. In such cases, the limitation is not the per-row exposure capability, but the extended temporal coverage of the image as a whole, which can complicate timing alignment and lead to unintended signal integration.

Global Reset Mode: A Practical Alternative to True Global Shutter

Some rolling shutter scientific cameras have a ‘global reset’ mode, also called ‘global reset release’ (GRR). This allows the camera to start the exposure of every row simultaneously – however, the end of the exposure ends on a rolling basis as normal for a rolling shutter camera. This can provide significantly faster response time when synchronizing camera acquisition with external events.

By aligning the start of integration across the sensor, global reset mode can significantly reduce timing uncertainty when synchronizing camera acquisition with external events. This makes it particularly useful for applications involving external triggers, pulsed illumination, or fast transient phenomena where response latency is critical.

However, global reset should not be confused with true global shutter behavior. Because exposure termination still occurs on a rolling basis, individual rows experience different effective exposure times unless illumination is carefully controlled. In pseudo-global shutter operation, uniform exposure across the image is only achieved when the light source is gated or pulsed to define a common exposure window for all rows.

Global reset mode therefore represents a practical compromise: it improves synchronization performance and reduces certain rolling shutter limitations, but it does not inherently provide the uniform exposure or geometric integrity of a true global shutter sensor.

Shuttering, Triggering, and Synchronization

In scientific imaging systems, shuttering does not operate in isolation. It is tightly coupled to how a camera responds to triggers and how its exposure timing aligns with external devices such as light sources, lasers, motion stages, or other cameras. Understanding this interaction is essential for achieving reliable synchronization and repeatable measurements.

Internal and External Triggering

A trigger defines when an image acquisition begins, but it does not, by itself, define how exposure is applied across the sensor. With internal triggering, the camera controls its own timing based on an internal clock, offering stable frame-to-frame intervals but limited coordination with external events. External triggering allows the camera to respond to signals from other system components, enabling precise alignment between exposure and experimental events.

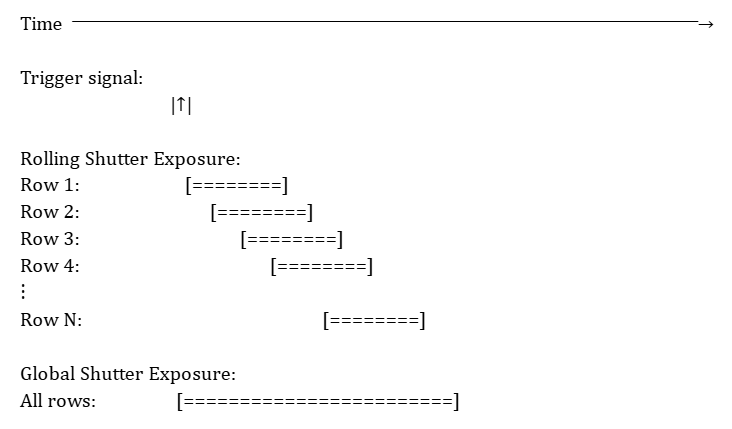

The effectiveness of external triggering depends strongly on the shuttering strategy. In rolling shutter cameras, a trigger typically initiates exposure for the first row, after which integration proceeds sequentially across the sensor. In global shutter cameras, the same trigger initiates exposure simultaneously for all pixels, producing a well-defined temporal relationship between the trigger event and the entire image.

Figure 3. Trigger and Exposure Timing in Rolling and Global Shutter Cameras

Timing Alignment and Latency

Trigger latency and timing determinism are often more critical than nominal exposure duration. Even when two cameras are set to the same exposure time, differences in how shuttering is implemented can lead to significant timing offsets within or between images.

Rolling shutter operation introduces an inherent temporal spread across the frame, which can complicate synchronization when imaging fast events or coordinating with pulsed illumination. Global shutter sensors eliminate this intra-frame timing spread, making them well suited for applications where precise temporal alignment is required across the full image or between multiple cameras.

Global reset modes offer a partial solution by aligning the start of exposure across all rows, reducing trigger-to-exposure latency. However, because exposure termination still occurs sequentially, uniform timing across the frame is only achieved when illumination is tightly controlled.

Synchronization with Illumination and External Devices

Many scientific imaging applications rely on synchronized illumination rather than continuous light. In these systems, the interaction between shuttering and illumination timing becomes critical. With rolling shutter sensors, uncontrolled illumination can result in uneven exposure across rows, while pulsed or gated light sources can be used to define a common effective exposure window.

Global shutter cameras simplify synchronization by allowing the illumination pulse to be aligned directly with a single, sensor-wide exposure interval. This deterministic behavior is particularly important for laser-based imaging, high-speed phenomena, and multi-camera configurations where timing consistency directly affects data validity.

Ultimately, synchronization performance is determined not by the trigger signal alone, but by how shuttering, readout timing, and illumination control work together as a system. Selecting the appropriate shuttering strategy therefore requires considering not only exposure requirements, but also how the camera will interact with the broader experimental setup.

Choosing the Right Shuttering Strategy for Your Application

Selecting an appropriate shuttering strategy is ultimately a question of timing requirements, not a simple preference between rolling or global shutter. The correct choice depends on how exposure timing, motion, illumination, and synchronization interact within a specific imaging system.

Rather than treating shuttering modes as universally “better” or “worse,” it is more useful to evaluate them against a small set of practical criteria.

When Rolling Shutter Is Sufficient

Rolling shutter cameras are well suited to applications where scene dynamics are slow relative to sensor timing, and where strict temporal alignment across the image is not required.

Typical examples include:

● Static or quasi-static samples

● Slow mechanical motion

● Continuous illumination

● Low-light imaging where sensitivity is critical

In these cases, rolling shutter operation often provides advantages in pixel efficiency and signal-to-noise performance, while artefacts and timing offsets remain negligible.

When Global Shutter Is Essential

Global shutter becomes necessary when temporal consistency across the entire image is critical to data integrity.

Applications that typically require true global shutter behavior include:

● Fast-moving objects or rapid deformation

● Multi-camera synchronization

● Laser-based or stroboscopic illumination

● Quantitative measurements where geometric distortion cannot be tolerated

In these scenarios, the simultaneous start and end of exposure across all pixels ensures deterministic timing and preserves spatial accuracy.

Where Global Reset Provides a Practical Compromise

Global reset modes can offer a useful middle ground when full global shutter sensors are not available or practical.

This approach is particularly effective when:

● Precise trigger-to-exposure latency is required

● Illumination can be tightly controlled or pulsed

● Short response time is more important than uniform exposure termination

However, global reset should not be treated as a direct substitute for true global shutter operation unless illumination timing is explicitly managed.

A Practical Selection Perspective

In practice, shuttering should be selected as part of a system-level timing strategy, rather than as an isolated camera feature. Exposure duration, frame rate, trigger behavior, illumination control, and sensor architecture all contribute to how time is encoded into image data.

A useful rule of thumb is:

● If what happens within a single frame matters, prioritize global shutter.

● If what happens between frames matters more, rolling shutter may be entirely sufficient.

● If trigger response time matters most, global reset can offer meaningful advantages.

By framing shuttering as a timing decision rather than a categorical choice, imaging systems can be designed to balance performance, complexity, and data reliability more effectively.

Conclusion

Shuttering in scientific imaging is fundamentally a question of timing control rather than a simple exposure setting. Differences between rolling shutter, global shutter, and global reset modes arise from how exposure is applied across the sensor in time, and these differences directly influence distortion, synchronization, and measurement reliability. No single shuttering strategy is universally optimal; the correct choice depends on scene dynamics, illumination control, and system-level timing requirements. By understanding how shuttering interacts with triggering and synchronization, imaging systems can be designed to balance performance, complexity, and data integrity more effectively.

If you are evaluating shuttering strategies for a specific scientific imaging application, discussing timing requirements and synchronization constraints at the system level can help clarify the most suitable approach. At Tucsen, we regularly supports researchers and system integrators in assessing shuttering behavior within real-world imaging setups.

Tucsen Photonics Co., Ltd. All rights reserved. When citing, please acknowledge the source: www.tucsen.com

2025/12/27

2025/12/27