Photon shot noise is a fundamental and key concept in the analysis of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in scientific cameras. Photon shot noise is a noise source that does not originate in the camera, but is inherent to the physics of light itself. It arises from the statistical nature of photon arrival and is therefore fundamentally different from electronic noise sources such as read noise or dark current.

Photon shot noise depends on the number of detected photons in a pixel, not on camera settings in a direct sense. As more photons are collected, the absolute shot noise increases, but it grows more slowly than the signal, leading to improved signal-to-noise ratio.

At sufficiently high light levels, photon shot noise can become the dominant noise source in an imaging system. Once this shot-noise-limited regime is reached, further improvements in image quality rely primarily on increasing the number of detected signal photons or reducing background-generated photon noise.

This article explains why photon shot noise occurs, how it is calculated, when it becomes the limiting factor in scientific imaging systems, and what engineering strategies remain effective once shot noise dominates.

Why Photon Shot Noise Happens?

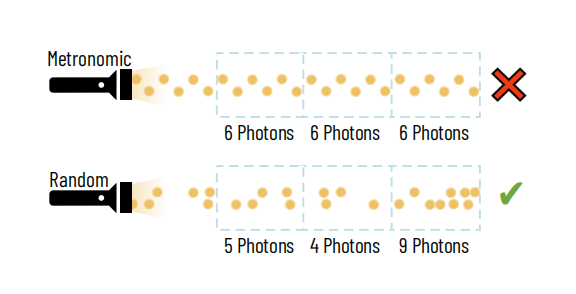

Figure 1: Physical origins of photon shot noise

Note: The emission, and hence also measurement of photons from practically all sources is random in time, not regular or metronomic. This means that successive measurements identical in length will result in different photon counts.

Regardless of the light source being measured—whether photons emitted by fluorescent molecules, light reflected from a sample, or photons generated by coherent or incoherent illumination—the underlying statistical behavior of detected light is the same.

Photons are discrete events, and their emission and arrival at the detector occur stochastically rather than at perfectly regular intervals. Even when the average photon flux is well defined, the exact number of photons detected within any finite exposure time will fluctuate from one measurement to the next.

This fluctuation arises because photon detection is fundamentally a counting process over a finite time window. For independent photon arrival events, the resulting photon count follows Poisson statistics, in which the variance of the measured photon number is equal to its mean.

This intrinsic statistical variation in photon counts is what gives rise to photon shot noise. Because it originates from the discrete and random nature of photon detection, it is present in all optical imaging systems and cannot be eliminated by changes in camera electronics or signal processing.

How Photon Shot Noise Is Calculated?

The variability from sample to sample (i.e. pixel to pixel or frame to frame) of how many photons are collected is our photon shot noise value.

Photon shot noise quantifies the statistical variability in the number of photons detected under identical imaging conditions. In practice, this variability appears as pixel-to-pixel or frame-to-frame fluctuations in the measured signal when the exposure time and illumination are held constant.

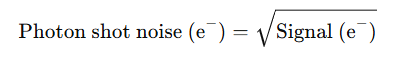

Photon detection is a counting process governed by Poisson statistics. For all Poisson-statistics noise sources, the noise (the standard deviation of successive measurements) is given by the square root of the mean number of events. This is approximated in practice by taking the square root of the number of detected photoelectrons: Our signal.

where Signal (e⁻) represents the mean number of detected photoelectrons collected in a pixel during the exposure. This expression assumes that the signal is measured in electron units; if the signal is recorded in digital units (ADU), it must first be converted to electrons using the system gain.

It can then be seen that although photon shot noise grows with signal, it grows more slowly than the signal.

When Does Photon Shot Noise Dominate?

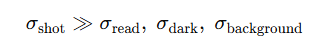

Photon shot noise becomes the dominant noise source when statistical fluctuations in the detected signal exceed all other noise contributions in the imaging system. In this case, photon counting statistics—not electronic or system-related noise—set the effective noise floor.

In a simplified noise model, the total noise per pixel can be expressed as the root-sum-square of individual contributions:

Photon shot noise dominates when:

Transition Between Noise Regimes

At low signal levels, imaging systems are typically read-noise-limited. In this regime, increasing exposure time or illumination yields limited improvement in signal-to-noise ratio, since read noise remains the dominant term.

As the detected signal increases, photon shot noise grows as the square root of the signal, while read noise remains constant. Once the detected signal exceeds the squared read noise, the system transitions into the shot-noise-limited regime. Beyond this point, SNR continues to improve with increasing signal, but only as √Ne , resulting in diminishing returns.

The exact transition point depends on detector characteristics such as read noise, gain, and quantum efficiency, as well as on optical throughput and illumination conditions.

Practical Implications

When photon shot noise dominates, the imaging system is operating near its fundamental physical limit. In this regime:

● Reducing electronic noise provides little additional benefit.

● Increasing analog or digital gain does not improve SNR.

● Image quality improvements depend primarily on collecting more signal photons or reducing background-generated shot noise.

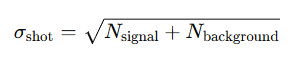

In many applications, background photons contribute significantly to the total shot noise. In such cases, the relevant noise term becomes:

Even when read noise is negligible, excessive background light can limit achievable SNR, making background suppression as important as increasing signal strength.

When Is Photon Shot Noise Important?

Although photon shot noise contributes to the noise budget at all signal levels, it becomes dominant in the signal-to-noise ratio calculation only when the detected signal exceeds the combined contributions of read noise and dark current noise.

From a purely mathematical perspective, this transition occurs when the signal approaches the read-noise-squared threshold. For a low-noise imaging system with approximately 1 e⁻ RMS read noise and negligible dark current, this condition is reached at signal levels on the order of a single detected photon. However, operating near this threshold is rarely meaningful in practice. At such low signal levels, differences in read noise between cameras and operating modes still have a substantial impact on achievable SNR.

A more practically relevant threshold for considering photon shot noise as the primary limiting factor occurs at signal levels approximately one to two orders of magnitude higher than the combined read noise and dark current noise terms. At this point, photon shot noise accounts for the vast majority of the total noise contribution in high-signal pixels.

For example, in a system with 1 e⁻ RMS read noise, this practical threshold occurs at signal levels on the order of 100 detected photoelectrons. In a system with 5 e⁻ RMS read noise, the corresponding threshold increases to approximately 2500 detected photoelectrons. These values illustrate that while photon shot noise may mathematically dominate at very low signal levels, it becomes an important engineering consideration only at substantially higher signal levels.

How to Tell If Your System Is Shot-Noise-Limited?

An imaging system is shot-noise-limited when photon counting statistics dominate the total noise budget. In practice, this can be determined by examining how measured noise scales with the detected signal under controlled conditions.

Noise Scaling with Signal

Under identical imaging conditions, increase exposure time or illumination and measure the mean signal and noise in a uniform region.

● If noise remains approximately constant as signal increases, the system is read-noise-limited.

● If noise increases proportional to the square root of the signal, the system is shot-noise-limited.

On a log–log plot of noise versus signal, shot-noise-limited behavior appears as a slope close to 0.5.

Signal Level Compared to Read Noise

A simple analytical check is to compare the detected signal level to the squared read noise:

where Ne is the mean number of detected photoelectrons per pixel and σread is the read noise in electrons RMS. When this condition is satisfied, photon shot noise dominates over read noise.

Limited Effect of Gain and Averaging

Increasing analog or digital gain does not improve signal-to-noise ratio in a shot-noise-limited system, as gain does not alter photon statistics. Similarly, frame averaging improves SNR only by increasing the effective photon count and cannot reduce photon shot noise below its fundamental limit.

Improving SNR in Shot-Noise-Limited Imaging

i) Collecting more photons

The only way to reduce the (relative) contribution of photon shot noise is to increase your detected signal.

For a given experiment and optical system, signal could be increased through choosing a camera with higher quantum efficiency, or larger pixels. If experimental variables such as exposure time or illumination light level can be controlled, this provides another avenue to increase SNR.

Importance of full well capacity (FWC)

The maximum SNR that a camera or camera mode can deliver can be approximated by the square root of the full well capacity. If you’re working in high light conditions or close to the full well capacity of your camera, this may become the primary limiting factor in the SNR you can achieve.

If your application requires particularly high SNR, seeking a camera with high full well capacity may be important.

ii) Reduce background light

A very important note is that photons hitting the camera will contribute shot noise no matter their origin. Many imaging applications have some degree of background light on top of their signals of interest. This background light will contribute to the shot noise in your signals of interest. But, it will dominate the noise in ‘dark’ regions of the image. This can greatly reduce contrast in images.

For example, if a background pixel has no photons hitting it, the range of values of that pixel will be determined by the read noise (and dark current where appropriate). For a modern sCMOS camera, this may be less than ±1.5e-. However, if just 4 photons of background light were to land on this pixel, this would contribute ±2e- of noise, outstripping the low read noise and reducing the contrast of the overall image.

From a signal-to-noise and contrast perspective then, it can be highly beneficial to reduce or cut out background light wherever possible.

Photon Shot Noise vs Camera Specifications

While photon shot noise is a fundamental physical effect, camera specifications determine how quickly a system reaches the shot-noise-limited regime and what signal-to-noise ratio can ultimately be achieved.

Once photon shot noise dominates, not all camera parameters remain equally important.

Quantum Efficiency (QE)

Quantum efficiency determines how many incident photons are converted into detected photoelectrons. Higher QE increases the detected signal for a given photon flux and therefore improves SNR even in shot-noise-limited imaging. QE remains one of the most critical parameters in this regime.

Read Noise

Read noise defines the signal level at which shot noise begins to dominate. Once the detected signal satisfies

further reductions in read noise provide little benefit, as photon shot noise sets the noise floor.

Full Well Capacity (FWC)

FWC limits the maximum number of photoelectrons a pixel can store. Because shot-noise-limited SNR scales as √Ne , the maximum achievable SNR is approximately set by the square root of the full well capacity. In high-light or high-SNR applications, FWC can become the primary limiting factor.

Other Parameters

Pixel size and gain influence how efficiently photons are collected and represented digitally, but they do not change photon shot noise itself. Their importance depends on system-level trade-offs such as resolution, dynamic range, and quantization, rather than noise reduction.

Can Photon Shot Noise Be Reduced by Averaging or Software?

Photon shot noise originates from the statistical nature of photon detection and represents a fundamental physical limit. As a result, it cannot be eliminated by averaging or software-based noise reduction.

Averaging and Stacking

Averaging multiple independent frames improves signal-to-noise ratio by increasing the effective number of detected photons. When averaging MMM frames, noise decreases as 1√M, while the mean signal remains constant.

This improvement does not reduce photon shot noise in a single exposure. Instead, it reflects the accumulation of more photon detection events across multiple measurements.

Pixel Binning

Pixel binning combines signals from multiple pixels, increasing the total detected signal and improving SNR in shot-noise-limited imaging. The underlying photon shot noise still follows Poisson statistics and scales with the square root of the total signal. Binning trades spatial resolution for improved photon statistics rather than reducing noise at a fundamental level.

Software Processing

Software processing can alter the visual appearance of noise, but it cannot change the underlying photon statistics. No post-processing method can reduce photon shot noise below its physical limit or recover information that was not captured due to insufficient photon counts.

Photon Shot Noise in Common Scientific Imaging Applications

The impact of photon shot noise varies across scientific imaging applications, depending primarily on signal level, background, and exposure constraints.

Low-Light Imaging (e.g., Fluorescence)

In low-light fluorescence imaging, photon shot noise often sets the fundamental sensitivity limit. Even with low read-noise cameras, image quality is typically constrained by the number of detected signal photons and background-generated shot noise.

Background-Dominated Imaging (e.g., Astronomy, Dark-Field)

In applications such as astronomical research or dark-field imaging, photon shot noise is frequently dominated by background light rather than the signal of interest. Once sufficient integration time is reached, background control becomes more effective than further reductions in electronic noise.

High-Speed Imaging

High-speed imaging often operates near the transition between read-noise-limited and shot-noise-limited regimes due to short exposure times. Photon shot noise dominates once adequate signal is collected within the available temporal window.

High-Flux Imaging (e.g., Bright-Field)

In brightfield microscopy imaging and high-throughput imaging, systems rapidly become shot-noise-limited. In this regime, full well capacity and dynamic range, rather than electronic noise, constrain achievable SNR.

Conclusion

Photon shot noise is a fundamental consequence of photon counting statistics and defines an unavoidable limit on image quality in scientific imaging systems. Once a system enters the shot-noise-limited regime, further improvements cannot be achieved through electronic noise reduction or software processing alone.

Correctly identifying this regime is essential for making effective engineering decisions. Before photon shot noise dominates, reducing electronic noise is critical; after it dominates, image quality improvements depend primarily on collecting more signal photons and minimizing background-generated shot noise.

Understanding how camera specifications such as quantum efficiency and full well capacity influence photon collection helps ensure that system optimization efforts target the true physical limits of the imaging process.

At Tucsen, we focus on helping users understand and optimize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of their imaging systems. If you would like to learn more about SNR-related concepts or discuss how to optimize the SNR of your imaging system, please feel free to contact Tucsen.

Tucsen Photonics Co., Ltd. All rights reserved. When citing, please acknowledge the source: www.tucsen.com

2025/12/08

2025/12/08