In scientific imaging, the brightest signal a camera can accurately record is not determined solely by exposure time or illumination, but by how much signal each pixel can accommodate before pixel saturation occurs.

The full well capacity of a pixel defines this upper limit. Once a pixel becomes saturated, its recorded intensity no longer reflects the true signal level, leading to measurement errors and loss of quantitative information.

As a result, full well capacity (FWC) plays a critical role in applications that require large dynamic range, where strong and weak signals must be captured simultaneously within the same image.

What Is Full Well Capacity (FWC)?

The full well capacity (FWC) of a pixel refers to the maximum number of photoelectrons that can be measured. In most cases, this limit is defined by the physical design of the pixel: detected photoelectrons are stored in a finite potential well during exposure, which can only hold a limited charge.

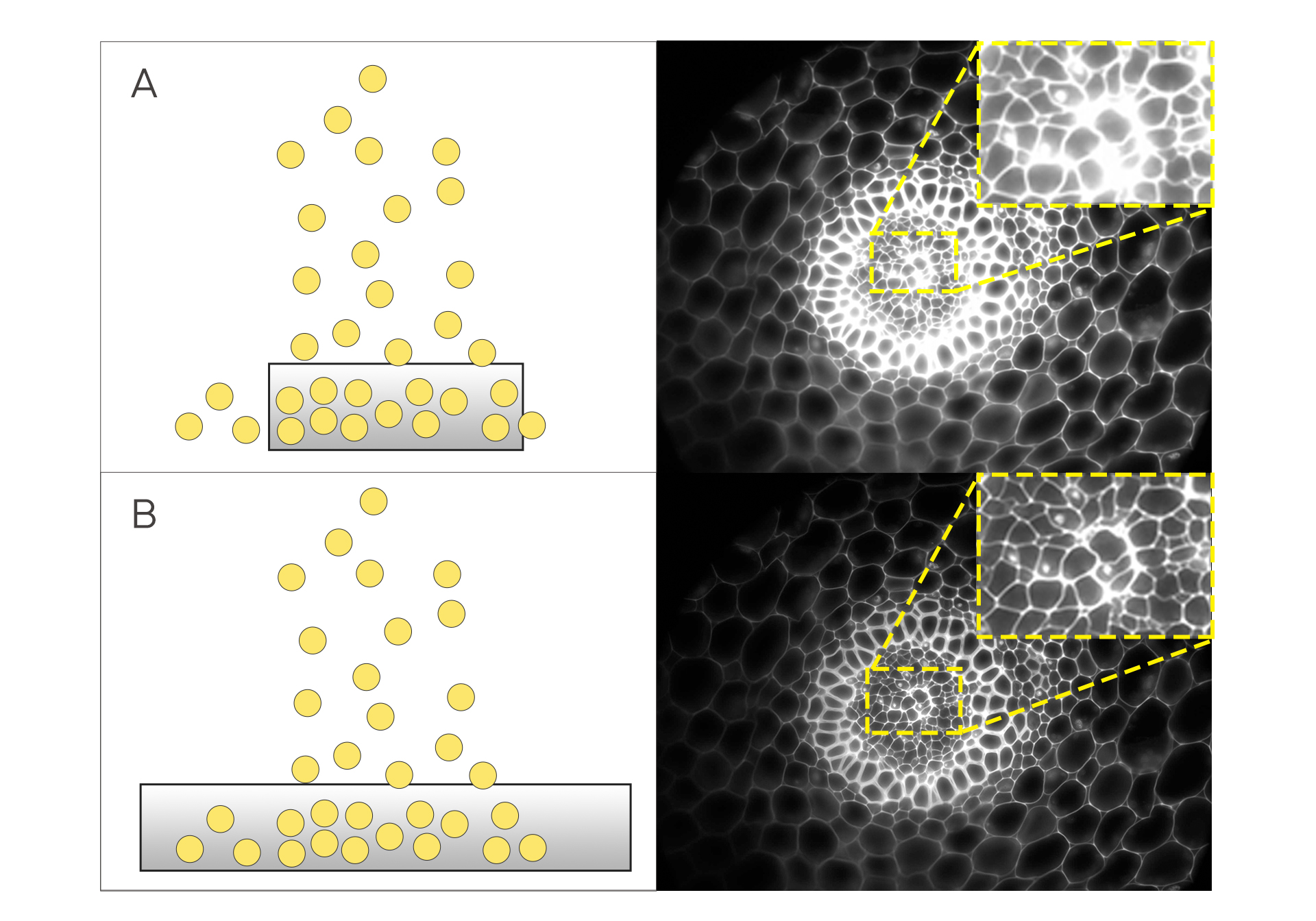

Figure 1. visualizes the relationship between full well capacity and dynamic range

(A) Low full well capacity causes the image to lose bright signal information.

(B) High full well capacity preserves signal information across the full intensity range.

As illustrated in Figure 1, higher full well capacity (FWC) expands the usable signal range and effective dynamic range.

At high signal levels, as the pixel well fills, the accumulated charge reduces the electric field within the potential well. This limits the pixel’s ability to collect additional photoelectrons and introduces non-linearity in the sensor’s response at high signal levels, often accompanied by a decline in effective quantum efficiency.

The term linear full well capacity (linear FWC) is used to describe the highest signal level at which no observable non-linearity occurs. This value represents the maximum signal that can be measured while maintaining a linear response to light, and it is the specification most commonly reported on scientific camera datasheets.

In practice, the term FWC is also used to refer to the saturation capacity or saturation signal, which is limited by bit depth and ADC resolution, defined by the maximum possible gray level determined by the camera’s bit depth.

While these values may coincide in some systems, scientific cameras often provide multiple readout modes with different ADC dynamic ranges. In such cases, lower bit-depth modes may access only a portion of the available physical FWC.

How FWC Works at the Pixel Level?

During image exposure, incident photons generate electrons within the silicon sensor. These electrons are collected and stored in the pixel well until the readout process occurs.

Each pixel has a maximum number of electrons it can hold. Saturation can occur either when the physical storage capacity of the pixel is exceeded or when the digital greyscale value reaches its maximum limit. Once saturation is reached, additional signal information is lost and can no longer be quantified accurately.

Full Well Capacity in Mixed Signal Scenes

Ideally, exposure time and illumination levels are configured to avoid pixel saturation altogether. However, this becomes challenging in scenes where bright and dim signals coexist within the same field of view.

Reducing exposure time or illumination to prevent saturation of bright regions often causes dim signals to fall close to the noise floor, making meaningful detection or quantitative measurement difficult. In such cases, noise can dominate the weak signal regions.

A higher FWC increases the usable exposure and illumination range, allowing dim signals to be detected more reliably without saturating brighter features. This directly improves measurement robustness in high dynamic range imaging scenarios.

(For a more detailed discussion of this relationship, see the Dynamic Range glossary section.)

When Full Well Capacity Matters Less?

In applications that operate exclusively under low-light conditions, or where dynamic range is not a primary concern, FWC plays a less critical role in camera selection and parameter optimization. In these cases, other factors such as read noise or sensitivity may dominate performance considerations.

Trade-Offs Between Full Well Capacity and Frame Rate

Some scientific cameras provide multiple readout modes, offering different combinations of frame rate, noise performance, and accessible full well capacity (FWC). In many cases, higher frame rates can be achieved by reducing the effective FWC.

This trade-off can be advantageous in high-speed imaging and low-light imaging scenarios where saturation risk is minimal. However, it requires careful consideration of signal levels and exposure margins to ensure data quality is maintained.

How Much Full Well Capacity Do You Need?

In imaging, higher image quality can often be beneficial, and can be improved both by increased signal to noise ratio and dynamic range. Both the maximum possible SNR, and dynamic range, that a camera can deliver are limited by the FWC.

However, in practice, only some imaging applications will reach the FWC of their cameras or camera modes. Typical scientific cameras can have full well capacities at least above 10,000e-, often around 30-80,000e-. Though some applications require very high FWC, in many applications requiring high-sensitivity cameras, signals will be many times (or even orders of magnitude) lower than these maximum values.

Example: Typical Maximum Signals in Different Imaging Applications

Different imaging techniques often have very different typical maximum signal levels. A given FWC is often achieved in a trade-off with other camera specifications, fitting camera or camera mode choice to the expected signal is wise. Below are some example maximum signals typically seen in different imaging applications.

● Single molecule imaging: 5-500e-

● Live cell imaging: 50-1000e-

● Spinning disk confocal: 20-1000e-

● Calcium imaging: 100-5,000 e-

● Fixed sample fluorescence documentation imaging: 2,000-20,000e-

● Brightfield/transmitted light imaging: 1,000-100,000e-

● High-intensity ambient light imaging: 1,000-100,000+ e-

Conclusion

FWC is often viewed as a sensor specification, but its significance extends to system-level imaging performance. Beyond defining the maximum measurable signal at the pixel level, FWC determines how much exposure and illumination flexibility an imaging workflow can tolerate before saturation or non-linearity occurs

FAQs

Why do images saturate more easily at high acquisition speeds?

At high acquisition speeds, exposure time and illumination margins become more constrained. If FWC is insufficient, bright regions reach saturation quickly, forcing shorter exposures that reduce overall dynamic range.

Why does increasing frame rate reduce usable dynamic range?

Higher frame rates often require shorter exposure times or different readout modes that limit accessible FWC. This narrows the usable signal range and increases the risk of saturation or noise-dominated measurements.

Tucsen Photonics Co., Ltd. All rights reserved. When citing, please acknowledge the source: www.tucsen.com

2022/05/13

2022/05/13